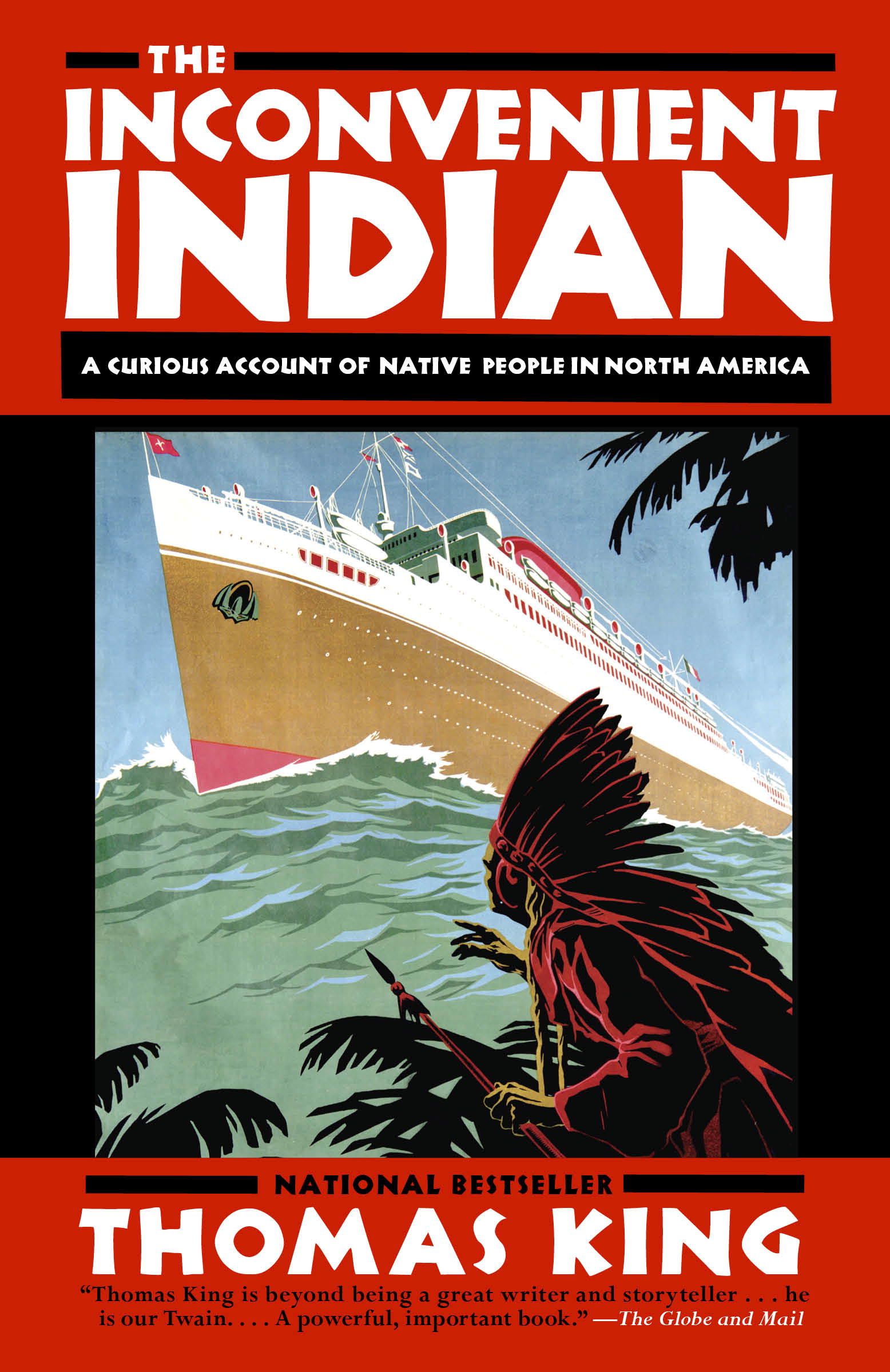

By calling attention to these somewhat reductive categories, King effectively highlights the ways in which uninformed narratives can skew the way people view each other, ultimately creating a disconnect between common perception and reality. King establishes these three categories of Indians to symbolize how years of systemic racism, exploitative federal policy, and cultural ignorance have oversimplified the North American perception of what it means to be a Native person. Lastly, “Legal Indians” refers to Indians as they exist according to government policy-that is, simply by virtue of their Indian Status and tribal affiliation. King suggests that Live Indians are invisible because they are “unruly” and “disappointing,” and many Americans feel uncomfortable acknowledging their own culture’s complicity in the problems Live Indians now face. These Live Indians are “invisible” to most of America because they do not conform to the stereotypical images of the Dead Indian, with the “noble” costuming and exotic, antiquated culture. King suggests that when most of America thinks about Indians, they think of an extinct relic of a bygone era: “all those feathers, all that face paint, the breast plates, the bone chokers, the skimpy loincloths.” “Live Indians,” on the other hand, refers to Indians as they actually exist. Thomas King, The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Thomas King, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. King’s term “Dead Indians” evokes the stereotypes and cliched images of Indians that exist in old Western films. The idea that either country gave First Nations something for free is horseshit.

These categories symbolize what King sees as a sharp disconnect between how North American culture perceives Native Americans and the reality of Native American oppression-a reality that goes unnoticed by the majority of the country.

King defines three categories of Indians that exist in real life: Dead Indians, Live Indians, and Legal Indians.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)